(Re)facing the future

- Chris Rogers

- Oct 11, 2024

- 6 min read

The words ‘face’ and ‘façade’ are connected etymologically but also practically. Just as the former tells us something about a person’s character, intent and, yes, age, so the latter gives us similar clues about a building. And as people change their appearance via make-up, hair or piercings, buildings do too thanks to the interventions of architects, engineers and makers. A fascinating discussion I attended last night demonstrated this across three recent case studies, whose subjects differed in period, typology and style but shared common themes.

The evening was organised by Architecture Today magazine and hosted by façade manufacturer Schüco whose products were used in all of the featured examples. AT’s editor Isobel Allen explained the session’s purpose as “Celebrating the collaboration between fabricators and designers,” and the importance of on-the-ground tweaks to previously-made plans become clear as those involved went through their projects. I learned something from each and illustrate this post with some snaps from the slide shows.

Residential – Reciprocal House, Hampstead

Gianni Botsford Architects were commissioned by the family of original owner Ron Hall to modify an early (1969) scheme by Norman Foster that added a contemporary extension to a period cottage, which stood on a tiny plot. Built simply in concrete block left unfinished with an exposed metal truss ceiling, Gianni Botsford joked that the way forward as finally agreed with his own client could be described as "extending an extension" as – unusually – the original house was now to be demolished and the Foster structure retained. This was then extended upwards and outwards with canted concrete fins forming two additional storeys, slatted to address privacy concerns and with oculi in the floors ensuring the penetration of daylight. This was critical since the site is almost surrounded – and significantly overshadowed – by mature trees, though both Foster and Botsford turned this into a positive by their treatment of the glazing.

Foster used large sliding doors to front the extension, flooding it with light and borrowing views of greenery to compensate for a negligible garden; Botsford described what his team found when investigating this solution as a system of "single glazed panes mounted on wheels and tracks, an ad hoc method that they seem to have invented” for the job. After the Foster studio (who were consulted, we were told in answer to my question from the floor) indicated they were “not precious about” that fabric but were keen on preserving its “spirit”, complete replacement was undertaken. I found this interesting as other one-off houses of the period, especially those of the High-Tech and wider Modernist movements, demonstrate the same bespoke approach with this kind of element yet architects and amenity bodies have differing views on how to address their inevitable deterioration. Then again, as I said to Gianni as we chatted afterwards, Foster was famous at that stage in his career for borrowing components and methodologies from other industries – marine, aircraft, car – and would I suspect have approved of updating those components as technology advances. Gianni noted that Patty and Michael Hopkins assisted at the time and of course built their own metal and glass house nearby. He also mentioned the Smithsons’ Upper Lawn as a reference. On completion the name Reciprocal House was coined, to reflect the conversation between the two generations.

Cultural – Bristol Beacon, Bristol

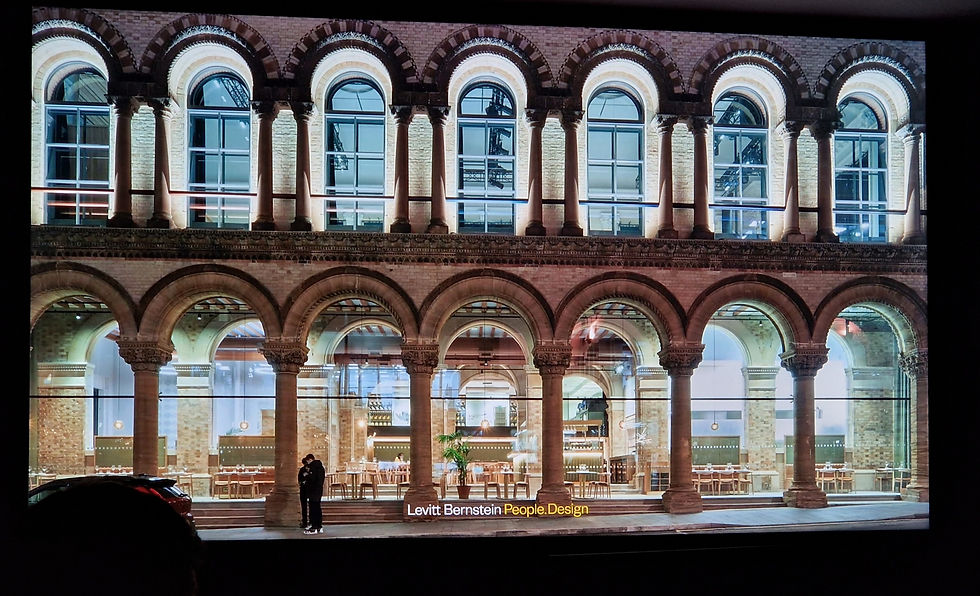

Once the Colston Hall but now the Bristol Beacon, this handsome Victorian Byzantine-style building suffered the indignity decades ago of having its windows removed and the large, arched openings bricked up following successive rebuilds and successive fires over the past century or so. Mark Fineberg of Levitt Bernstein architects explained just how complex a task reinstating these windows was as part of a plan to improve the convert venue’s facilities and upgrade the building as a whole, given no plans or written details had survived down the ages. There was however a determination on all sides to achieve an outcome that was both architecturally sensitive and technically proficient when doing so.

High-quality period photographs were the start point; ingeniously, these were analysed in minute detail to extrapolate everything from the size of bricks to the possible employment by the original builders of a form of double glazing, with logical deduction and some subtle aesthetic tweaks contributing to the final design. Highly complex programmatic demands for sound insulation, light-tightness, flexibility and more as well as the latest regulatory requirements forced further consideration, and even on the ground the reality of such an intervention prompted additional effort: all the sills were at different heights, it turned out, so the new glazing and associated frames had to be measured and made individually. But as Mike said of the contractor, "they're like blacksmiths, they make stuff" and this was evident in their own exertions. The slides we were shown of the multi-layered, beautifully finished windows that now fill the reopened spaces were very impressive, each part working – as Mark said – very hard to accomplish the overall goal. Such cross-fertilisation has proven rewarding however beyond the Beacon – the contractor’ specialist experience of installing ballistic glass, for example, has been valuable on another Levitt Bernstein project where frameless glass has to be let into the reveals.

Workplace – The Parcels Building – Oxford Street

Britain’s high street is always changing, as I’ve noted, so the recladding of one of its existing commercial buildings to refresh and update it is not a surprise. But an autopsy of the rather public remodelling of this post-war block just across from Selfridge’s, in contrast to similar work happening in my own sphere of interest, the oddly-invisible-to-many City of London, seemed a chance too good to miss.

TP Bennett were executant architects for this scheme by Grafton, and it was clear that the knotty core was how to achieve the overall aesthetic desired – and heavily advocated – by those design architects in the face of many challenges. Adding extra floors, a modest sideways expansion and various other small moves were easy enough; at issue was the removal of the original façade of pre-cast concrete panels and replacement with a state-of-the-art equivalent. Careful consideration of Daniel Burnham‘s pioneering department store was a given, not least as Selfridge’s was the owner and client, and Mark Brighouse, Associate Director of TP Bennett, noted that the new elevations were accordingly “reinterpreted architecturally in relation to” the American precedent, along the Duke Street return as well as the Oxford Street frontage. The final design, using angled fins, addressed this whilst controlling solar gain and increasing daylight.

When disassembly of that original façade revealed a range of cautionary points, whether unexpected ‘toes’ or projections of the floor slabs or poorly-made reinforced concrete, a revisit was necessary of the proposed new façade system. A pre-cast concrete carrier with stone facing was modified in favour of hand-set stone only for many of the piers, saving weight but still requiring the invention of ‘hugging brackets’ to wrap around the existing structural columns and to which those new panels could be attached. Tying in all the necessary parts to the building in a way that minimised stresses and directed the loads down verified paths was also key. As the completed panels weighed around 5 tonnes each, including 700kg of glass, installation was a concern on such a busy site even without the attention to detail required to meet the 1-2mm tolerances between those parts specified by Grafton. As Mike observed, the practice was focused on “what's it going to look like, not how you build it.” The solutions included a clever and deliberate “inconsistent coursing” of the stone to conceal movement joints. Each piece was shaped in a computer-aided design programme and cut from that digital file in a factory; on site, each was set one at a time. At ground level even the doors – created from catalogue parts but stretched – needed testing, with a pull test required to ensure their robustness. Mike and I talked about these problems in more detail afterwards and I must nip along to see the building itself when I get the chance.

This was an absorbing evening that shed light on just how hard it is to ensure buildings that need to change face the future.

Comments