Fragments of a hologram rose: Re-seeing Blade Runner

“The postcard is a white light reflection hologram of a rose […] Holding it carefully between thumb and forefinger, he lowers the hologram toward the hidden rotating jaws. The unit emits a thin scream as steel teeth slash laminated plastic and the rose is shredded into a thousand fragments […] Parker lies in darkness, recalling the thousand fragments of the hologram rose. A hologram has this quality: recovered and illuminated, each fragment will reveal the whole […] from a different angle”

- Fragments of a Hologram Rose by William Gibson, first published 1977

++ This is one of five linked articles on this site. Find each from the subject pages for architecture, film, television, design and art ++

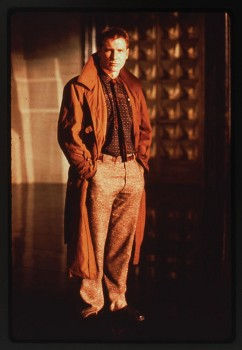

Deckard (icollector.com)

Batty (ripping-ozzie-reads.com)

Rachael (snowce.tumblr.com)

Gaff (hungdrawn.blogspot.com)

Tears in rain Memories of missing words, stories and concepts

One November day on the streets of Los Angeles, at a little after a quarter to five in the afternoon, a retired police detective has his sushi meal interrupted. He is detained by a former colleague, taken to precinct headquarters and coerced into accepting a job: “The last census showed a hundred and six million people in the city; somehow in the crowd I was supposed to find the four phoney ones”. So begins Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. Or so it would have begun, had that line of dialogue from one version of the voice-over narration survived the editing process.

Fittingly for a story whose very essence is the question of what is real and what is not, much of Blade Runner’s attraction revolves around its ambiguities, apparent and actual errors, and the fragments of imagery, words and music from concepts discarded during production and Philip K. Dick’s source novel that remain embedded in the finished film. This article explores those memories.

Time to die

Undoubtedly the best-known complication which arose from the film’s troubled history is confusion over the exact number of replicants at large in the city. Dick’s novel begins with eight, with Holden eliminating two before he is wounded to leave six, and accounts for all of them as it progresses. The original film begins with six but jumps quickly and unaccountably to four. The explanation lies in the deletion of Mary, the fifth replicant, at an early stage due to budget constraints and a pressurised shoot unable to close the gaps left in the narrative as a result.

Another numerical difficulty is presented by the year in which the film is set. The replicants may have a four-year lifespan but seem strangely concerned with the imminence of their demise (“How long do I live?”, asks Leon) given incept dates of 2016 or 2017 and a setting, according to the opening credits, of 2019. The answer is that the film was actually scripted as taking place in the year 2020 until audience research seemingly indicated potential confusion with the term ‘20/20 vision’. The date was changed for the credit sequence but it was too late to alter the rest of the chronology.

An ambitious rival

Edward James Olmos put considerable work into creating the personality of Gaff, whom Scott has described as a 2019 version of a 1970s pimp, choosing unsettling bright blue contact lenses to alter his own dark eye colour and inventing the character’s Cityspeak dialect.

In the script Japanese was specified as the language in which Gaff’s words were to be verbalised on set, but Olmos rejected this as insufficiently original and instead personally researched and accurately translated each part of the text into either German, French or Hungarian for use when acting his scenes. Unfortunately many were cut or truncated and the longest, rather ironically, saw his lines replaced by Deckard’s voice-over narration.

Here, then, is what Gaff actually said in the film’s opening scene, where he finds Deckard at the White Dragon noodle bar, and that longer speech, which occurs during their Spinner flight to the precinct. Both reveal a considerable amount of the personality and motivation of a character Scott has described as well-named (gaff: ‘a hook used esp for landing large fish’ – Chambers).

GAFF: You will be required to accompany me, sir

Deckard doesn't understand. He turns back to his food.

GAFF: If you do not comply with an official request, I will be obliged to exert my authority

Deckard is ignoring Gaff but the counterman leans in and translates.

GAFF: To defy constituted authority is to flout the public good

Deckard doesn't understand a word.

COUNTERMAN: He say, you under arrest, Mr Deckard.

Deckard turns back to his food.

DECKARD (Turning to Gaff, loudly): You got the wrong guy, pal.

GAFF: Captain Bryant ordered me to bring you in even if I have to serve you like sushi

When Deckard hears "Captain Bryant," he winces. It's all over even before the counterman launches into a rambling free-form translation spiced with creativity. Deckard looks disgusted and resigned.

----

Deckard's view of the street. Deckard is sitting in the passenger seat. He watches the maze of suspension bridges, platforms and catwalks swim by below. The tops of larger buildings are emblazoned with fluorescent numerals and scrawls of neon ads.

INTERIOR: SPINNER, NIGHT

Deckard is sitting gloomily in the passenger seat, still eating from his bowl with chopsticks as Gaff manoeuvres the spinner through the city canyons.

GAFF: I told Bryant I could take care of this myself. Just move me up. I'll do the job, I told him. Five phonies. I just air 'em out. (He imitates shooting) Bow! Bow! Bow!

Deckard looks at Gaff uncomprehendingly.

GAFF: But no, he says. Bryant thinks you're hot shit, smartest spotter, baddest Blade Runner. You don't look so hot to me. Don't even shave. Bad grooming reflects on the whole department. You don't dress well, that reflects on me. . . Makes the whole department look like shit. The skin jobs look better than you do! What's the point of wiping out skin jobs if they look better than Enforcement? Pretty soon the public will want skin jobs for Enforcement. I guess you'd prefer that, huh? That why you quit?

Deckard looks at Gaff. He hasn't understood a word. Gaff glares and mutters, turning his attention to navigation of the spinner.

GAFF: Exactly! Whatta jerk! If I wasn't up for promotion I'd put this baby in a hot spin and leave your dinner all over the glass!

The spinner flies low along the centre of a busy street and then turns right…

A song to buy a drink to

Shaken after his battle with Zhora, Deckard buys a bottle of Tsingtao – a real-world brand – from a street kiosk. A haunting, crackling, doo-wop-style song, playing on an unseen radio, drifts over the bustling crowds: ‘One more kiss, dear/One more sigh…’ This song was composed by Vangelis as part of the film’s score, yet is clearly radically different from the rest of the Blade Runner soundtrack. Understanding why comes from appreciating Scott’s original wishes for the scene.

Scott is a fan of The Ink Spots, an African-American group popular between the wars. He had already used one Ink Spots song, I Don’t Want to Set the World on Fire, for his ‘Share the Fantasy’ television commercial for Chanel No. 5 perfume a few years before, and now wanted to employ their 1939 release If I Didn’t Care for Blade Runner.

Although it was included in the Workprint, copyright clearances unfortunately proved impossible to secure for the released film. Undeterred, Scott asked Vangelis to create a new composition based on the unusable original. With well-known British singer-songwriter Peter Skellern providing the lyrics, the result is an homage that matches If I Didn’t Care almost exactly in structure, tempo and style. Don Percival sung the song on theatrical release prints, with John Bahler performing that duty on the controversial New American Orchestra soundtrack recording.

Undressed to kill

During the climactic pursuit of Deckard by Batty, the replicant pauses for a moment on a window sill. Clearly visible on his upper torso are a series of circular marks in geometric patterns. Though not explained in the film, these are a legacy of another concept present in early drafts of the script and which reached a high state of development before being abandoned.

The fleeing replicants were originally to be seen in a shuttle floating offshore, illustrating Bryant’s words in his briefing to Deckard at the beginning of the film. As part of this scene Batty – a combat model, remember – was to be shown removing cybernetic battle armour attached to his body by tubes and interface cables. Never filmed, a remnant of that lost idea can now be glimpsed in the pursuit scene.

The menagerie

A wealth of birds, animals, fish and insects is encountered in Blade Runner. They feature as references in dialogue, as elements of the production design, as set dressing and as props. They are most apparent in Leon’s Voight-Kampff test and two scenes in the Tyrell Corporation pyramid: Deckard and Rachael’s exchange over the owl, and Rachael’s own test.

The viewer is left to assume some parallel with the human genetic engineering that made the replicants. In fact, the answer lies in Dick’s novel. One of its fundamental themes is the rarity of animals in the future. The apocalyptically-named World War Terminus has laced the city with radioactivity and killed most of the local fauna. The animals that remain are affordable only by a few; the rest buy a mechanical replica. This evidence of the value of animal life did not survive the transition from novel to film, allowing more room for the value of human life to be explored and leaving a perplexing menagerie wandering the pages of the script.

Tortoise – the first question for Leon in his Voight-Kampff test

Turtle – “Same thing”

Fish – clearer in the Workprint, this is the main ingredient of Deckard’s favourite meal at the White Dragon noodle bar. He ate it again later in the film in a now-deleted scene

Chicken – Gaff’s first origami sculpture, and his first message

Owl – Tyrell’s display model, as demonstrated by Rachael. A stylised owl is also the logo of the Tyrell Corporation, just visible on Tyrell’s housecoat. The pieces of the chess set with which Sebastian plays Tyrell are also, as far as can be seen, owls (Tyrell's, appropriately, are men). This is one of the first missing links with the novel. In it, “no one today remembered why the war had come about or who, if anyone, had won. The dust which had contaminated most of the planet's surface had originated in no country and no one, even the wartime enemy, had planned on it. First, strangely, the owls had died. At the time it had seemed almost funny, the fat, fluffy white birds lying here and there, in yards and on streets; coming out no earlier than twilight as they had while alive the owls escaped notice. Medieval plagues had manifested themselves in a similar way, in the form of many dead rats. This plague, however, had descended from above.” That owls are mythologically associated with both wisdom and impending disaster should also be noted.

Cow, butterfly, wasp, bear, spider, oyster, dog – all appear in Rachael’s Voight-Kampff test, although the cow is implied (“calfskin wallet”) and the bear is another missing link; the infamous “replicant or a lesbian” question as heard in the film carries an obvious sexual frisson but, in concluding with Rachael’s indignant reply of “I should be enough for him”, only an oblique relevance in the context of a Voight-Kampff test. The actual point of that question has been lost by omission of its final line, which can now only be found in the novel: the girl in the magazine photograph is lying on a bearskin rug. It is thus not Rachael’s verbal response to a potential sexual fantasy of her husband’s that is being weighed, but her involuntary bodily reaction to the skinning of a creature rare even before the war. The final question, about the stage play banquet, confirms her replicant status albeit, yet again, in a way not clear in the finished film; her eye shows horror at the idea of raw oysters, but no reaction at boiled dog, whch humans would foind more repulsive.

Snake – the nature of the scale found in Leon’s apartment’s bathtub; its owner is seen wrapped around Zhora shortly after

Ostrich, pony – both are seen being manhandled as Deckard looks for the snake maker’s shop. This section of the fictional Los Angeles was termed Animoid Row in pre-production material, and was intended to be a market for live and simulated animals. Many others are seen in the sequence

Rat – in Sebastian’s apartment. A deleted scene showed Pris playing with them

Unicorn – Gaff’s, and the film’s, final message

____________________________________________________________________________

Posted May 2012